Following last week’s Autumn Statement, David Ward considers the political considerations guiding Jeremy Hunt’s economic measures, the parallels between the Conservatives’ strategy in 1992 and today, and the ‘very tough’ choices facing Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves.

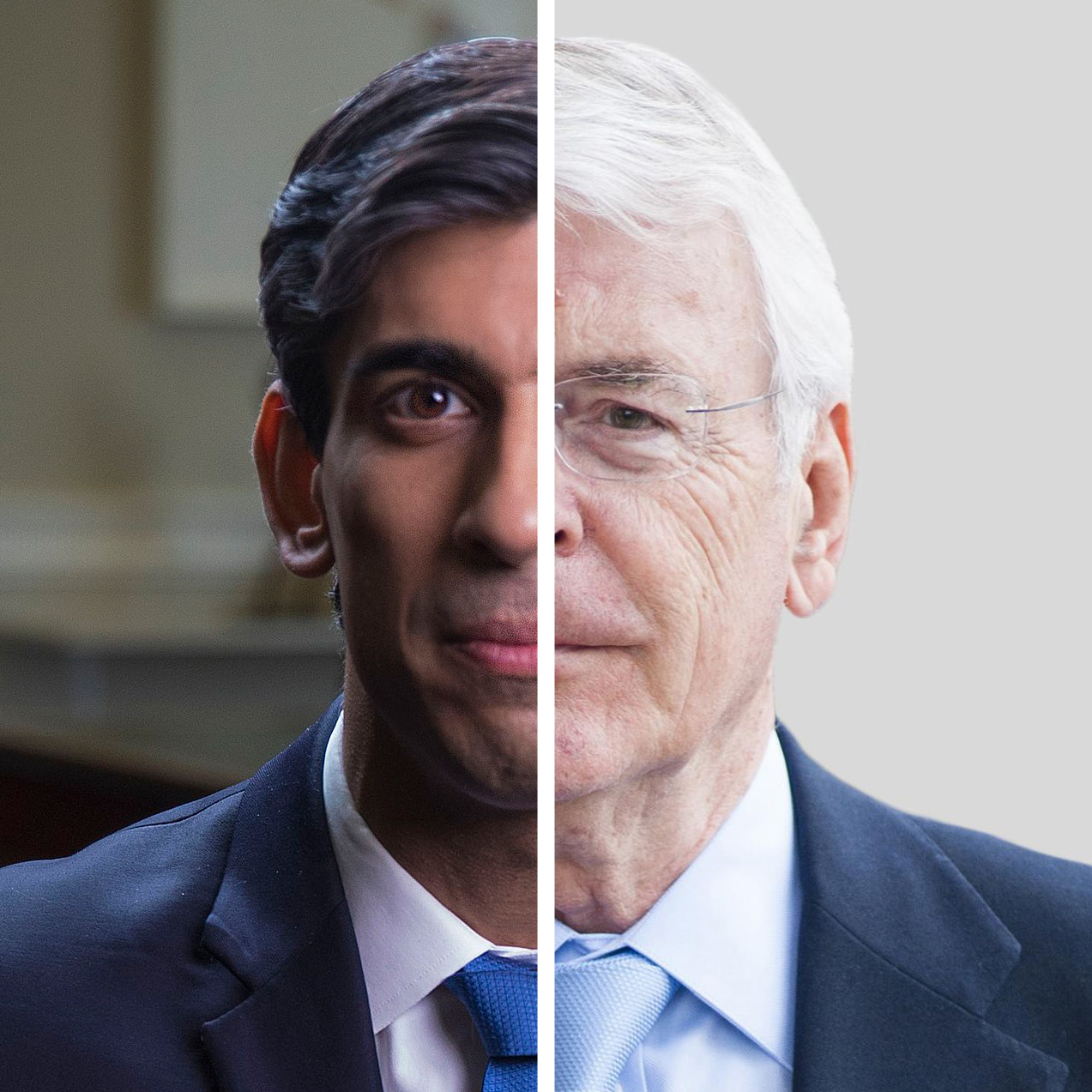

Forget the idea that Rishi Sunak is a Thatcherite. All his political hopes and fears are embodied in John Major. Sunak desperately wants to emulate Major the general election winner of 1992, rather than the loser of 1997. That’s why the Conservatives are already starting to borrow from their successful 1992 campaign playbook – and it’s also why Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves should study the election that Labour lost in 1992, rather than the party’s landslide win in 1997.

At this year’s Labour Party conference, I briefly met Keir Starmer and suggested to him that the Shadow Cabinet should war-game the 1992 election. He looked alarmed for a moment and then agreed that it was ‘a good idea’ – I hope Keir and his leadership team are acting on my suggestion. If so, they should concentrate on the Conservatives’ strategy – at least as much as how Labour lost – because in the run-up to the 1992 election, the Tories were very successful in sowing doubt about Labour’s fitness for office using tactics that they will surely repeat ahead of the next election in 2024.

The similarities between 1992 and the next election are striking. For Sunak, they raise the tantalising prospect that he can succeed in plucking victory from the jaws of defeat, just as Major did. In early 1992, the UK economy was starting to show signs of recovery from a deep recession, with both interest rates and inflation receding. Major and his Chancellor, Norman Lamont, could argue that Labour risked killing off these ‘green shoots’ of economic recovery.

Crucially, Major – who had succeeded Margaret Thatcher in November 1990 – pulled off the trick of looking like the leader of a new government even after 12 years of Tory rule. He killed off the hated ‘Poll Tax’, successfully negotiated ‘opt outs’ from the Maastricht Treaty, and was able to present himself as a fresh start.

As a result, Labour’s poll lead at the end of Thatcher’s premiership dissipated and the election held on 9 April 1992 seemed too close to call. Many expected Labour to either win narrowly or be the largest party in a hung parliament. Major’s outright victory with a working majority of 21 was a surprise. Against the trend of the polls, the Tories won 42.8 per cent of the vote, only a fraction down on their performance in 1987. It would be a dream come true for Sunak to repeat such an unexpected success. His nightmare is that he is doomed to be the John Major of Black Wednesday.

30 years ago, the Pound was ejected from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), despite the Bank of England spending billions in reserves and announcing a rise in interest rates to 15 per cent. As a result, the Conservatives’ economic credibility was shredded. Labour quickly soared to a huge lead in opinion polls that proved unassailable all the way to Tony Blair’s landslide win in 1997. It is hard to fathom how the Conservatives have managed to recreate another market crash at least as dramatic as Black Wednesday, but that is what Liz Truss’s short-lived premiership and disastrous ‘Mini Budget’ achieved. In September, the markets turned against them, causing a run on the Pound, higher interest rates, and a massive intervention by the Bank of England to ensure the solvency of the pensions system. Just as the markets did not have faith in Major’s ability to maintain the Pound’s high rate in the ERM, they did not believe in Truss’s ‘dash for growth’ based on unfunded tax cuts for the rich.

Unsurprisingly, the Government’s economic credibility and the Tory Party’s poll ratings have again nosedived but, unlike Major and Lamont after Black Wednesday, Truss and Kwarteng have not survived in office – and Sunak is now distancing himself from Truss, as Major did with Thatcher after 1990. Now, Sunak and his Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, are seeking to erase the Mini Budget from public consciousness and have joined hands with the Treasury and the Bank of England to metaphorically dance on the grave of Trussonomics.

Just as John Major buried Thatcher’s signature ‘Poll Tax’, Jeremy Hunt has now cancelled Kwasi Kwarteng’s proposed abolition of the top rate of tax. In a dramatic 180-degree turn, the Autumn Statement lowered the threshold for the 45p rate to increase the number of taxpayers that will have to pay it. The Government is also accepting, uncritically, the Office for Budget Responsibility’s estimate that there is a £50 billion ‘black hole’ in the public finances and the fiscal gap can be closed by freezing tax thresholds.

The ‘tough love’ Autumn Statement is a political gamble – dressed up as economic necessity – which Sunak and Hunt hope will save the Conservatives from the electoral annihilation that current poll ratings portend. By raising taxes now, they are trying to discourage the Bank of England from raising interest rates much higher. Postponing the main spending cuts until after the next election is also designed to shorten the period of recession. They can also expect inflation to be falling. In short, Hunt and Sunak need the ‘green shoots’ of recovery to be sprouting again by August 2024 which would allow them to reassure voters that they have taken ‘tough choices’ and navigated the storm – re-running the Conservatives’ 1992 tactic of portraying Labour as a threat to recovery and a risk too far.

My prediction is that the Conservative Party will closely follow its successful attack on Labour in the run-up to the 1992 election, which began in January 1991 when the then Chief Secretary to the Treasury, David Mellor, and Tory Chairman, Chris Patten, claimed that Labour’s policy pledges amounted to an extra £35 billion per year. Launching the ‘Labour’s going for broke again’ poster campaign – developed by Saatchi and Saatchi and run on 1000 sites across the UK – Mellor and Patten claimed that would mean 15p on the basic rate of tax, equivalent to an increase of £1000 per year for people on average earnings.

The Tories kept repeating variants of this attack all the way to the election and culminated in their ‘Tax Bombshell’ and ‘Labour’s Double Whammy’ posters which warned of higher taxes and prices. These exaggerated claims completely ignored the costed commitments to increase the state pension and child benefit that had been made by the Shadow Chancellor, John Smith, but nevertheless were given extensive coverage in the pro-Tory tabloids.

The Conservatives’ final throw of the dice ahead of the election was Norman Lamont’s budget (held just before the dissolution of Parliament) which was the opening shot in the election campaign proper and was predictably designed to create the maximum difficulty for Labour. The Chancellor announced the creation of a 20p tax band for the first £2000 of disposable income and was presented as a first step towards eventually reducing the basic rate from 25 to 20 per cent. For a government that had lavished tax concessions on the rich for more than a decade, this was a cynical attempt to appear concerned about the low-paid. However, it still caused a huge problem for the Opposition and, while it seriously disrupted Labour’s planned proposals for the Shadow Budget, Neil Kinnock and John Smith quickly agreed that they had to support the 20p rate.

In the two years ahead, it is highly likely that the Conservatives will seek to maximise the difficulties for Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves in the same way. Watch this space for a new Conservative costing of Labour’s policies, obtained by trawling through all the Shadow Cabinet’s speeches, and interpreting every criticism of government neglect as a firm spending commitment. Look out for the Autumn Statement of 2024 which will become another budget based on a fresh OBR assessment with a high probability of some ‘surprise’ symbolic tax cuts. It will be a crucial opportunity for Sunak and Hunt to try to ‘bribe’ the voters, shoot Labour foxes, pose awkward fiscal choices, and then immediately call an election.

Likewise, delaying the largest public expenditure cuts until after 2024 – and setting up awkward choices for Reeves – is a prime example of Hunt playing the ‘election game’. Depending on the revised OBR forecast in less than two years’ time, Labour will be challenged to either accept or reverse whatever spending cuts remain, to be funded either through tax rises or additional borrowing. The latter, however, will be difficult for Reeves, having already made a clear commitment to an additional annual £28 billion of green capital investment – which is a core component of Labour’s growth strategy. It will surely be essential to robustly argue the case for additional borrowing for investment to meet the public’s expectation to ‘Build Back Better’ after Covid, overcome the failures of Brexit, and meet the ongoing challenge from climate change.

Having worked for John Smith when he was Shadow Chancellor and then Leader of the Opposition, I understand that the choices for Starmer and Reeves will be very tough. Whilst economists can legitimately argue about the size of fiscal ‘black holes’, the Opposition often have to battle through media perceptions and market expectations that are often far from rational or even economically literate. Despite these obstacles, I am optimistic that Labour will decide Sunak’s ‘Major Dilemma’ in 2024.

I do not think that the Conservatives will escape the consequences of ‘Trussonomics’, nor do I think that a recovery from the current recession and the record fall in living standards will be enough to deliver a repeat of John Major’s 1992 victory. Labour looks set to return to power, but its messaging and policies will have to be well-targeted, highly disciplined, and able to anticipate Tory attacks. That is why a close study of that election will be time well-spent for both Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves – forewarned is forearmed.